Until around the 2000s, research on vitamin D in dogs focused entirely on the development of puppies’ bones. Recommendations for vitamin D in dogs are practically entirely based on the work of the research duo Hazewinkel and Tryfonidou on calcium and Great Dane puppies. From there, the rule of 500 IU/kg in food was applied to dog nutrition.

It is realistic to state that the amount of vitamin D in dog kibble is entirely based on a few extreme studies on bone development disorders. It was only about 10 years ago that research expanded into other areas, investigating the connection between low vitamin D and conditions such as cancer, including mast cell tumors, heart and kidney diseases, or intestinal diseases similar to IBD in dogs.

Two basic issues weaken, and even hinder, research on vitamin D in dogs.

Firstly, there is no knowledge of what the vitamin D levels in dogs should be. Dogs have approximately the same levels as humans, so the limits have been borrowed from human standards. However, even in humans, there is consensus only about the lower limit, which begins to cause rickets. What would be considered normal is entirely unclear. Typical values are reasonably well known, but there are significant variations, possibly between breeds and genders, and certainly due to diet.

Secondly, it is unknown how much vitamin D dogs actually receive. Most dogs eat kibble, and no one knows how much vitamin D is in them. Likely, even manufacturers, except for a few larger corporations, do not know how much vitamin D is in their food.

The amount of added vitamin D is known, but even that is not widely disclosed today. The total amount of food consists of meats, fats, organs, and added vitamin D, minus production losses.

I have often said that since manufacturers no longer want to disclose more than the legally required minimum information (after all, consumers are not meant to know, only to pay), we should use the standardized goals set by FEDIAF. Every complete feed must meet them.

The problem arises with the range of recommendations. FEDIAF allows 13.8 – 80 µg (553 – 3200 IU) per kilogram of dry matter, and if using American foods, AAFCO has given a range of 12.5 – 125 µg (500 – 5000 IU) per kilogram of dry matter.

It is then entirely up to the manufacturer how much vitamin D is genuinely in the dog food. The situation either improves or worsens depending on the portion sizes the dog eats.

For raw feeders, it is slightly easier because they can use human nutrition databases and supplement analyses as some sort of guideline. However, if using organ mixes, fish in any feed form, or meats with organs ground in, the amount of vitamin D the food provides is entirely unknown.

We are missing three essential things in Finland (as well), if one wanted to determine a truly justified amount for dogs:

- we do not know what the vitamin D level should be, i.e., what we are aiming for

- we do not know how much vitamin D the dog even receives

- dog vitamin D levels are not measured

So if you are impatient and do not want to read further, the tldr answer to the question in the title is: no one knows, which is why it is advisable to give raw-fed dogs and those on a 50/50 diet 0.7 µg/kgBW, and for those eating only kibble, it is somewhat easier – perhaps no vitamin D supplement is needed at all or give about 0.4 µg/kgBW.

Basics of Vitamin D

Let’s review the basics so that everyone is roughly on the same page.

A dog (and a cat) does not get vitamin D through UVB radiation from the sun, like humans, horses, or cattle. I encountered yet another veterinarian’s claim about the importance of the sun. The longevity of this misconception is utterly astonishing, as the true state of affairs was known as early as 1961, when Wheatley and Sher did not find the 7-dehydrocholesterol required for vitamin D production in the lipids of dog skin. Great Dane puppies were once again sacrificed on the altar of science when Hazewinkel et al. (1987) left them entirely without dietary vitamin D, causing rickets. The condition was not corrected with UVB lamps. In polar regions, the differences between day and night are maximal, so Griffiths and Fairney (1988) traveled to the South Pole to take blood samples from huskies, and also from seals and penguins. The sled dogs’ 25(OH)D or vitamin D storage levels did not follow the sunny and dark rhythm but the diet – in fact, they had the least vitamin D during the bright times. How et al. (1991) used slightly more advanced techniques and found some 7-dehydrocholesterol, but the amounts of the vitamin D precursor produced were insufficient. At the University of Sydney in Australia, Laing et al. (1999) studied the 25(OH)D levels of Greyhounds and mixed breeds brought in for educational purposes over two years, and there was no seasonal variation.

One single study claims that a dog does not need vitamin D from food. Kealy et al. (1991) left Pointer and German Shepherd puppies without vitamin D, but the food contained 14% calcium and 1% phosphorus. The puppies did not develop rickets or other observable bone disorders over two years. However, the researchers did not even know if there was vitamin D in the food because it was not analyzed, but it did contain organs. Additionally, when a tenfold overdose of calcium is given, passive absorption is ensured. The study also lasted too short a time to know the effects in adulthood.

Vitamin D Metabolism

Vitamin D obtained from food is not inherently usable in its tasks. Vitamin D is captured from food and transported through the intestinal wall carried by a special transport protein to the dog’s liver. In the liver, vitamin D is enzymatically converted into 25-hydroxyvitamin D, commonly known as calcidiol and abbreviated as 25(OH)D. It is stable and inactive, meaning it can be stored and does nothing. The half-life of 25(OH)D varies with consumption, other metabolism, the individual, and many other factors. However, within 10 days to a few weeks, its amount halves, so the actual vitamin D stores are not as large as thought. This means that in about two months, the stores are depleted. 25(OH)D is what I often refer to as the storage form of vitamin D for clarity and simplicity.

There is about a thousand times more 25(OH)D in the blood circulation than the active form, making it easier to measure. Additionally, it has been reliably established that it reflects the amount of vitamin D obtained from food (and through the skin in humans), so from the amount of 25(OH)D, it can be determined whether too much or too little vitamin D has been obtained. It is possible to measure the so-called vitamin D levels in dogs, but very few veterinarians do so even when the information would be crucial for treatment. However, it is absurdly priced, which may deter interest – Movet charges around 100 euros. For comparison, the private sector Puhti Lab charges 50 euros for humans, and Mehiläinen about 75 euros.

When actual active vitamin D is needed, the parathyroid gland secretes parathyroid hormone, which instructs the kidneys to convert 25(OH)D into the actual active compound, whose more complex name is 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D or 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol, but most often the name calcitriol is used and abbreviated as 1,25(OH)2D. It is the actual hormone-like form, which is meant when it is said that vitamin D does this and that. There is very little calcitriol, and since it does things and is produced only as needed, calcitriol is not measured to determine deficiencies or excesses. Additionally, its half-life is short, only about 4 to 6 hours. Again, for ease and comprehensibility, I often refer to it as active vitamin D.

Vitamin D Levels

In Finland, the unit nmol/l is used. Especially in American studies, the unit ng/ml is used instead. When you want to convert ng/ml > nmol/l, multiply the nanograms by 2.5 (it gives an approximate value but is close enough). If the conversion needs to be done nmol/l > ng/ml, divide by 2.5.

All mammals have the same levels, and the general perception is that the target values would also be the same. Thus, in dogs, a deficiency is considered to be below 50 nmol/l, a sufficient intake is about 80 nmol/l, and a good amount is over 100 nmol/l. Movet (big private lab-corporate for animals in Finland) uses reference values of 50–365 nmol/l, and most often in the literature, one encounters 60 – 215 nmol/l, which comes from Michigan State University’s veterinary laboratory services. This means that the range is remarkably wide.

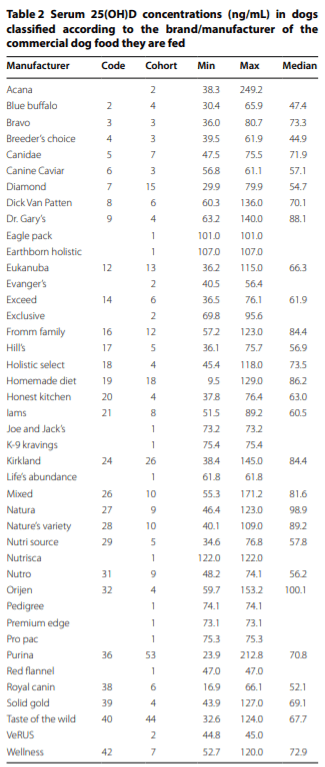

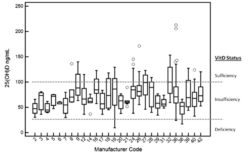

Sharp et al. and Foods

Sharp et al. (2015) attempted to determine from 320 dogs how their vitamin D levels correlated with feeding. It was found that 25(OH)D varied between 23.8 – 623 nmol/l. Some clearly had a deficiency of vitamin D, while the highest value indicated a severe overdose of vitamin D according to current understanding – although each dog was clinically healthy.

Variation in Foods

292 dogs reportedly ate commercial food from 40 different brands. In American texts, it is never clear what this means, but it is about complete feeds, and in this case, most likely kibble. Homemade food, which is equally vague as a concept, was eaten by 18 dogs. A mix of both, in a way a 50/50 diet, was given to 10 dogs.

292 dogs reportedly ate commercial food from 40 different brands. In American texts, it is never clear what this means, but it is about complete feeds, and in this case, most likely kibble. Homemade food, which is equally vague as a concept, was eaten by 18 dogs. A mix of both, in a way a 50/50 diet, was given to 10 dogs.

The median of 25(OH)D (i.e., the midpoint of values) varied significantly between different commercial food brands, 118.5 – 250.3. Of course, there were not many subjects per food brand, but still, this means that most of those who ate complete feeds had sufficient vitamin D levels.

With homemade food, the situation was more varied, which was to be expected. Complete feeds are always constructed according to AAFCO standards in American markets, but with homemade types, the owner is responsible for the vitamin D intake in one way or another, and it is not automatic as with complete feeds. The lowest value was 23.8 nmol/l, and the highest was 322.5 nmol/l.

When comparing those eating homemade food as a whole to those eating a specific commercial food, and removing the extremes, those eating commercial food had higher 25(OH)D levels. However, when the comparison was changed to all those eating homemade food versus all commercial, and again removing the extreme values, there was no significant difference overall between homemade and commercial.

This means that some commercial food had more vitamin D or was eaten more. Another brand had less, or the portion size was smaller. This culminates in the fundamental weakness of Sharp’s research. It is not known or disclosed

- how much vitamin D was in the food

- how much each dog ate

Supplements

About a third of the dogs received some supplements. Fish oil, salmon oil, and separate vitamin-enriched dog biscuits were used, but Sharp does not specify how supplement use was distributed across different feeding methods.

There is a clear difference from Finnish dog feeding. If you randomly take almost 400 owners interested in their dogs’ health and nutrition at some level (a basic requirement to participate in such a study, which also easily causes bias, distortion), the proportions of different feeding styles are different, and the use of supplements is significantly broader.

Sharp does not specify the difference between fish oil and salmon oil, nor how much vitamin D the products contained. He also does not differentiate between dog biscuits or their nutritional content, even though there are large differences between products.

Compared to those who did not use supplements, there was practically no significant difference with fish oil and dog biscuits. Dog biscuits caused greater variability and slightly better levels for some, but since it is unknown what and how much the dogs ate, the result is meaningless. It is clear, however, that no substantial advantage was achieved in principle. Or maybe there was, if supplements achieved the same 25(OH)D levels with homemade food as kibble, but even Sharp did not seem to consider that relevant information.

Dogs using salmon oil had 25(OH)D levels on average 49 nmol/l higher than without salmon oil. This is not surprising, but it must be kept in mind that it is unknown what this time salmon oil contains.

Breed and Gender Differences

There were three breeds. There were 144 German Shepherds, 8 White Shepherds, and 168 Golden Retrievers. Age did not affect vitamin D levels, but breed did. When Sharp removed the too high and too low values from the results, German Shepherds had higher 25(OH)D levels than Golden Retrievers. Both individual extremes, the lowest and highest values, were both Golden Retrievers and ate homemade food.

Intact males had significantly better vitamin D levels than intact females when comparing medians: males at 208.3 and females at 169.3 nmol/l. This may be explained by larger food portions for males, giving them relatively more vitamin D than needed when calculated by metabolic weight. Again, it comes down to not knowing how much the dogs ate and what foods. One explanation may be the types of foods fed to males and females, as without research, I claim that there are differences – whether that difference has any real significance depends on many factors. Hormonal differences, such as estrus and testosterone, can also affect the matter.

However, males also had a wider range starting from 59.8 nmol/l, which is at the deficiency threshold, all the way to 623 nmol/l, indicating an overdose. Females had narrower variability, but it was also wide: 80.8 – 357.5. This would lightly suggest that differences arise from feeding.

When comparing intact males to neutered ones, those who lost their testes had lower vitamin D levels, with a median of 151 nmol/l. Neutered males reached the upper values in their range similar to females, but the lowest value was a deficiency level of 42.3 nmol/l.

For spayed females, the situation was somewhat similar to males. When reproductive ability was removed, the median dropped to 154.5 nmol/l. However, the difference was remarkably minimal. At the upper end of the range, the difference was equally minimal, but for spayed females, it was higher, but at the lower end significant. The weakest value for a spayed female was 23.8 nmol/l, indicating a more severe deficiency.

For males, the significance of neutering for weight gain is less, but it exists, often due to reduced activity. When food is reduced, or switched to so-called leaner food, vitamin D intake also decreases. Of course, lower-fat and consequently lower total energy foods should not automatically be condemned as inferior in terms of protective nutrients, but that is normal recipe policy in kibble. When activity decreases, the intake of protective nutrients is also considered to decrease, so less is added to foods.

For females, spaying significantly affects hormones controlling metabolic rate, so calculated schematically, energy consumption drops by about 20% the moment the uterus is left in the veterinarian’s hazardous waste bin or at least the ovaries are severed. Weight gain in spayed females is a common concern for owners, and it is fought by reducing food. Reducing food automatically reflects, for example, in a collapse of the vitamin D status if not corrected separately. According to Sharp, none of the 320 dogs were given vitamin D separately.

The same weight gain issue for females is also visible at the other end as improved intake. But again, we encounter Sharp’s fundamental problem: without knowing what and how much the dogs ate, it is impossible to seek an explanation from food or metabolic rate. It can be influenced by something as simple as the coat fluffing after spaying. Owners have tried to improve coat quality with salmon oil, simultaneously increasing vitamin D.

Deficiency or Adequate Intake

Sharp speculates about the significance of feeding and nutrition on the obtained values. If he had planned his study even at a basic level to try to clarify the things claimed to be investigated, the speculation would have been less. I am a very science-friendly person, but this same certain lack of professionalism is visible in several basic dog studies and always when the topic is dog feeding. The same problem is found in Finland, where even doctoral dissertations are based on this.

Sharp pauses for a moment to wonder why salmon oil improved dogs’ vitamin D status, but fish oil did not. He even ponders bioavailability for a moment. This would not have needed to be pondered if he had bothered to look at product labels in the nearest local supermarket. Then he would have discovered the differences between cod liver oil and omega-3 fat supplements. The task might have been slightly easier if he had asked the owners what they were giving and how much they were giving. Also, dividing supplements into something other than generic groups might have been beneficial.

The contribution of the study, however, was that in American dog feeding culture, most dogs had good or very good vitamin D status. It can even be argued that regardless of how the kibble manufacturer has emphasized their recipe, sufficient amounts of kibble do not lead to a vitamin D deficiency in dogs – at least not in healthy dogs.

The fact that in homemade feeding – which includes our raw feeding – a dog’s vitamin D status depends entirely on what the owner puts in the food bowl should not be a surprise.

Sharp et al. define a good level as at least 100 ng/ml, which is 250 nmol/l. They justify it with human studies, which indeed report the same limit as 40 mg/ml or 100 nmol/l. I got a strange feeling that perhaps the studies used as references were not read again. Only one study that Sharp relies on sets the good intake limit at over 250 nmol/l, and it was a canine cancer risk study by Selting et al. 2014, which has been criticized, among other things, for setting the limit solely based on parathyroid hormone function, without genuinely investigating the diet of the dogs involved in the study, other blood values, urine tests, or anything else that would have clarified the health status. Sharp generally takes a reasonably positive approach to the health effects of vitamin D.

By deciding that the good intake limit is more than double what the rest of the world considers, Sharp concluded that most dogs were deficient in vitamin D. If 40 ng/ml or 100 nmol/l is taken as the limit, most dogs actually had sufficient vitamin D. A good example of why you can never trust what studies say, but should always look at what was genuinely studied.

By deciding that the good intake limit is more than double what the rest of the world considers, Sharp concluded that most dogs were deficient in vitamin D. If 40 ng/ml or 100 nmol/l is taken as the limit, most dogs actually had sufficient vitamin D. A good example of why you can never trust what studies say, but should always look at what was genuinely studied.

The reason Sharp’s group took a fairly uncritical view of Selting’s group’s claims may be very simple. Sharp was involved in Selting’s study, and most of the dogs were the same. These are the kind of little details that must always be considered. The same is found in Finland, and interesting connections can be found in Viikki (Veterinary Medicine at the University of Helsinki) theses and licentiate studies, nowadays even in doctoral dissertations, regarding both the results and claims about the supervising and approving person and their work.

Hookey et al. and Diet Food

Obesity is perhaps the biggest, if not the biggest, health problem in developed countries today, affecting both owners and dogs. In Finland, the situation is better than in the United States, but still, we diet slightly overweight dogs with diet foods designed for morbidly obese dogs in the American market. The significance of obesity and dieting for vitamin D levels is unclear, and Hookey et al. (2018) at the University of Missouri’s veterinary school attempted to investigate this.

The study recruited dogs owned by staff and students. The dogs were clinically healthy, and if they had not been previously spayed or neutered, it was done at the start of the study (note: where does the current obsession among future and current veterinarians to automatically remove reproductive organs come from?). Some dogs were of normal weight, some slightly overweight. A total of 14 dogs completed the study, albeit at different times. A few dropped out for various reasons.

This was a Purina study, and Overweight Management was used as the diet food, with its magical numbers being 27/6.5. According to Purina, the vitamin D content was 40.17 µg/kgDM. However, the study also analyzed four samples of the food and did not rely solely on the manufacturer’s claim:

- Vitamin D2: < 1 µg/kgDM

- Vitamin D3: 39.5 – 47.75 µg/kgDM

Purina had thus succeeded reasonably well in standardizing the vitamin D amounts.

The control group ate the same Purina food, but in amounts that maintained their weight. The portion size was not disclosed. For the test group, it is not stated how much the dogs ate, but the portion was such that the dogs lost weight safely. Now it would be necessary to guess whether the manufacturer’s recommendations were followed or if the dogs’ portions were increased because they were constantly hungry. Spaying and neutering also significantly affect the situation, although the control group’s hormonal function was also addressed.

The dogs lost weight on Purina food. I do not consider this particularly noteworthy when energy intake is reduced, and the dogs are switched to 6% fat. I would have been much more interested in the long-term effects, but that was not studied here – but Purina got the opportunity to advertise that according to scientific and clinical studies, Overweight Management causes weight loss in as little as seven weeks.

D-Status Improved Slightly

In the control group, the starting median 25(OH)D was 185 nmol/l, with a range of 115 – 275 nmol/l, and the dieting group started with practically the same values. By the end of the study, the controls had also slightly improved, with the median rising to 215 nmol/l. For those dieting on Purina, the change was somewhat larger: median 287.5 and the range was 222.5 – 407.5 nmol/l.

The study mentions one interesting detail. As the study neared its end, one dog needed about 33% more energy to maintain the correct body fat percentage. At the same time, it received exactly 33% more vitamin D from its food. For another case, energy had to be increased by as much as 52% to stop the weight loss. Similarly, its vitamin D intake rose by 52%.

This means two things that are self-evident. Diet foods may be too light, especially with recommended portions. When talking about kibble, the intake of all nutrients depends entirely on the grams put in the bowl, meaning that small portions for dieting can easily lead to deficiencies in everything else, not just energy.

One hypothesis of the study was that since some vitamin D is stored in fat, losing fat releases vitamin D. There are research lines worldwide with the opposite idea: too low vitamin D makes you fat or at least facilitates weight gain. In the study, all dogs improved their vitamin D levels, but those dieting improved more. This would allow speculation about the significance of weight loss in improving vitamin D levels. However, Hookey notes that when they removed the significance of diet, vitamin D levels did not change with weight loss, and the only thing they confirmed was the significance of diet in vitamin D intake.

When the actual intake from foods for the dogs was converted to correspond to metabolic weight, the dogs received 1.3 – 4.4 times more vitamin D than recommended by the NRC. With a schematic generalization, this would mean that raw-fed dogs should be given 0.33 – 1.1 µg/kgBW to achieve the same as some kibble has genuinely provided. Poochie Revival’s recommendation of 0.7 µg/kgBW no longer seems so exceptional.

If it is assumed that those receiving the least vitamin D also had the lowest measured 25(OH)D levels, it would mean that every dog would need to receive at least 1.5 times more than what the NRC recommends to reach the good lower limit of 100 nmol/l.

The study also had its stumbling block, which was everything else the dogs ate. One of the dieting dogs received fish oil at the same time. Another received two grams of anchovy/sardine oil per day and was measured at 195 nmol/l. In the control group, two dogs received fish oil, and one received four grams per day, achieving 130 nmol/l with food. One dog received two grams of fish oil and was measured at 245 nmol/l. Hookey does not mention the weights of the dogs in his examples. It is different to give two grams of fish oil to a five-kilo dog than to a 50-kilo dog.

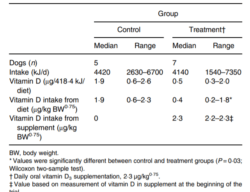

Young & Backus and the Ineffectiveness of Supplements

The starting premise of the study was at least peculiar, more accurately the goal. Young and Backus (2016) wanted to determine how well vitamin D supplements improve dogs’ 25(OH)D levels, as so many have a deficiency of vitamin D.

How surprising, as they too had taken the deficiency limit as the 100 ng/ml or 250 nmol/l proposed by Selting et al. Is it surprising that Backus was part of Selting’s research group? This is genuinely concerning. When one single researcher in the world recommends a 2.5 times higher level as the limit for good intake, the other members of the research group expand it in their own work to be the deficiency limit and claim with clear eyes that it is the generally accepted limit.

This gives us a demonstration of how science’s very own memes are born. Raisins are not an exception.

25(OH)D was measured from 46 dogs, and 33 of them were below 250 nmol/l (71.7%). Of these, 13 were recruited for the study. 6 dogs received olive oil as a placebo daily, and 7 received a vitamin D supplement at a dose of 2.3 µg/kgME, which corresponds to just over 1 µg/kgBW. The study lasted 10 weeks, and the dogs’ 25(OH)D was measured four times.

The dogs were of different sizes and breeds, males and females with and without reproductive organs. Feeding was asked from the owner, and of the 13 dogs selected for the study, 12 had known feeding – at least somehow, although the pair uses the expression Complete diet histories were available. 11 ate kibble, one apparently something else.

The dogs were of different sizes and breeds, males and females with and without reproductive organs. Feeding was asked from the owner, and of the 13 dogs selected for the study, 12 had known feeding – at least somehow, although the pair uses the expression Complete diet histories were available. 11 ate kibble, one apparently something else.

For some reason, Young and Backus divided feeding by energy. However, it does not tell the portion size, which is an essential factor when considering how much vitamin D is obtained from food or even trying to describe food variability per dog.

They reported the estimated vitamin D intake. It is likely guessed based on what the manufacturer has reported as the added vitamin D amount, although they incorrectly refer to analyses of the finished product (these are all inaccuracies that begin to erode credibility). The method is entirely functional when the food does not contain raw materials that provide significant amounts of vitamin D.

Young and Backus themselves realized that their control and test groups received very different amounts of vitamin D from food. I do not understand the logic of continuing with that setup, but they probably encountered the situation only after the owners were recruited. In the control group, the median for vitamin D from food was 1.9 µg/kgME, with a significant range of 0.06 – 2.3 µg/kgME. In the test group, the median was a meager 0.4 µg/kgME, with a range of 0.2 – 1.8 µg/kgME.

Only at the end of the study, in weeks 9 and 10, was there a statistically significant improvement in 25(OH)D levels with vitamin D compared to the placebo group (could someone more familiar with the scientific world explain to me what the placebo served here?). Statistical significance means in real life that at the start of the study, the median 25(OH)D of the test group dogs was 178.25 nmol/l, and at the end, after the given vitamin D supplement, it was slightly higher, and the value had to be guessed from the bar chart because the researcher duo did not find it necessary to disclose it.

At week six, according to the chart, the control group’s 25(OH)D levels dropped by the same amount as the test group’s rose – so according to the chart, the change did not occur in weeks 9 and 10, as they stated, but three weeks earlier. The reason was not speculated, so perhaps it was not statistically significant, even though the consistently stable values suddenly changed and remained stable again until the end of the study.

Nothing substantial remains from Young and Backus’s work. They do not find any real thoughts on why a vitamin D supplement higher than what kibble provides did not affect the median 25(OH)D amounts. I will not even try to guess because the studied groups were so fragmented, and the collected data reveals nothing. Averages are useful only when it is known what they consist of. Therefore, it is not even possible to entertain the idea of how regulation might have affected the matter, because the 250 nmol/l limit is so absurd, or whether lower 25(OH)D levels are perhaps metabolic questions, not to mention external factors.

According to the study, however, D3 vitamin as a supplement is useless, but the same D3 vitamin added to kibble works.

To Supplement or Not?

The studies provided some sort of absolution for at least some kibble and reinforced the knowledge that in raw feeding, the owner must take responsibility. The problem with kibble in the studies was that the vitamin D stores of the eaters varied greatly, and it is unknown why. Whether it is due to the grams of food eaten or the manufacturer’s recipe remains a fairly open question. More likely, it is both, with the rest coming from the dog’s metabolism.

The world may have changed over time. At the University of Sydney, the vitamin D levels of Greyhounds and mixed breeds were studied over two years in the late 1990s (Laing et al. 1999). At that time, all the dogs were either deficient or below good intake, with values ranging from 10 – 76 nmol/l. However, I do not believe that at that time, Australians would have fed in any exceptional way, but of course, many competitive Greyhounds were fed like our 50/50 is today, and vitamin D supplements were not widely used. Current studies did not find such a bad situation.

If you want to do it right, you should measure the dog’s 25(OH)D or the storage form of vitamin D. If the amount is below 100 nmol/l, the dog’s vitamin D dosage should definitely be increased. When exceeding 200 nmol/l, everything is fairly well, and at 300 exceedances, one might even consider leaving the supplement on the shelf – reaching some mega amounts of 600 nmol/l in studies is certainly not achieved with just food.

The problem is that testing costs money. At least two tests are needed, actually three, and they cost a hundred euros a shot without a veterinarian. I am curious, but not that curious. Until I get rich, I am content with knowing that kibble dosages are sufficient to achieve vitamin D levels, and I dose vitamin D from a bottle in raw feeding following the 0.7 µg/kgBW rule and give slightly less to those eating only kibble.